Letters from the Baltic

In the mid-nineteenth century, European peoples began a movement toward self-definition in terms of “national” or “ethnic” distinctions. It was an age of social upheaval and change. With the industrialization of the Baltic region (modern Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia), indigenous ethnic groups began to replace Baltic Germans, Polish-speaking elites, and Jews in towns and cities. These same urbanized populations were subject to the Russification policies of the later tsars and developed a greater sense of their own identity in response. As national consciousness arose, resistance to imperialism took the form of increased interest in folk traditions—music, literature, dance, dress, and a revival of pre-Christian religious traditions in institutional form.

The principle of national self-determination shattered several empires in the First World War,

leading to independence for Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland on the Baltic, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia in eastern Europe, and Ireland in the western fringe. The

Second World War led to a comparable process of decolonization in

Asia, while the shocking of Soviet collapse split Czechoslovakia in two and splintered Yugoslavia into eight new nation-states.

You are a dark amulet set in Lithuania.

Old grey writing—mossy, peeling.

Each stone a book; parchment every wall . . .

Yiddish is the homely crown of the oak leaf

Over the gates, sacred and profane, into the city

Grey Yiddish is the light that twinkles in the window.

Like a wayfarer who breaks his journey beside an old well,

I sit and listen to the rough voice of Yiddish.

—Moyshe Kulbak, “Vilne,” 1929

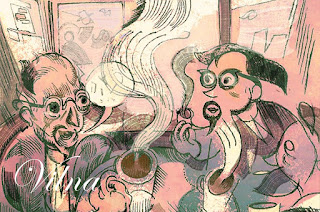

Local Jews, called Litvaks, made up a third of the population of interwar Vilna. The preceding century of Russian rule had patterned their language and culture, and when Vilna became a city of the Second Polish Republic, Litvaks continued to see Yiddish, the language of the folk, as an essential aspect of Jewish national identity. Neither Polish nor Hebrew but Yiddish became the language of Jewish cultural, academic, and political life.

“Vilna would not be Vilna if its soil did not produce any literary offspring,” wrote the scholar Zalmen Reyzen in 1929. The movement in Vilna produced the poets Avrom Sutskever, Chaim Grade, and Shmerke Kaczerginski, the historian Moshe Lewin, and the parodist Leyzer Volf. It was the inheritor of Poland’s “Yiddish language charmer” I. L. Peretz. In Warsaw at the time, two-thirds of Jewish dailies were printed in Yiddish, including the Haynt and the Yiddish Bilder, and Warsaw studios produced dozens of Yiddish films: village melodramas, ghost stories, and musicals.

At a 1935 YIVO conference, Noyekh Prilutski declared Yiddish “a territory, an anarchic republic, with its capital in Vilna.” YIVO, the Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut, was established there in 1925, and the acronym is still in use despite the change in name to the Institute for Jewish Research and the relocation to New York City.

Postnote: Germany occupied Vilna (modern Vilnius in Lithuania) on 24 June 1941, and by 6 September had established the big ghetto for useful workers and the small ghetto for the sick and infirm. The small ghetto survived only a month before being extinguished on 24 October. The big ghetto was liquidated in late September, 1943, and 14,000 Jews were deported to other labor camps. The last Jews in Vilna were killed in July 1944, with the Red Army at the gates. Of 58,000, only two or three Jews remained by the end of the war.

if there is a sick child to the east

going and nursing over them

if there is a tired mother to the west

going and shouldering her sheaf of rice

if there is someone near death to the south

going and saying there’s no need to be afraid

if there is a quarrel or a lawsuit to the north

telling them to leave off with such waste

when there’s drought, shedding tears of sympathy

when the summer’s cold, wandering upset

called a nobody by everyone

without being praised

without being blamed

such a person

I want to become

—Miyazawa Kenji (1896-1933)

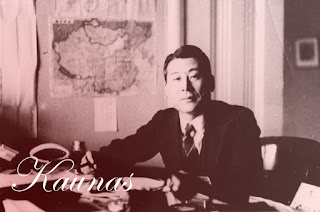

Sugihara Chiune, Japan’s vice-consul to Lithuania, awoke to find over a hundred refugees on his doorstep. Most were Polish Jews, fleeing the German occupation. The only way out was to cross Soviet Russia and embark to Japan for transit further abroad, and the Soviets would only grant exit permits to those with the necessary transit visa.

Japan’s Foreign Ministry urged adherence to strict requirements and procedures, wary of offending their German allies. Sugihara did something which even now is rare: He ignored his orders, set aside diplomatic and professional concerns in the awareness of human suffering. “You want to know about my motivation, don’t you?” he said later. “Well, it is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them.” He referred to a samurai maxim: “Even a hunter cannot kill a bird that flies to him for refuge.”

In the days that remained to him before the Soviet occupation forced the closure of his embassy, he produced over 2,140 handwritten visas, throwing the last of them from the window as his train steamed toward Berlin. His last act was to pass his official stamp to a forger, and his last words, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

Sugihara’s humane intervention helped thousands flee the carnage in Europe; they sailed from Vladivostok to the Tsuruga port, and from Yokohama or Kobe to the US, the countries of the British Commonwealth, and Palestine. When Sugihara’s widow Yukiko traveled to Jerusalem in 1998, she was met by scores of tearful survivors who showed her the yellowing visas that her husband had signed.

This story is well-known in Japan—the subject of nine plays and six TV dramas. “As a fellow Japanese person, I am enormously proud of his courageous and humanitarian actions,” said Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in January, standing at the desk where “Japan’s Schindler” wrote thousands of visas in open defiance of his government’s cautious nativism. Between those two interests, Abe’s government shows a clear affinity for the latter, and Sugihara’s independent action is simultaneously praised and assiduously avoided. In 2017, in the midst of the worst refugee crisis since the Second World War, Japan admitted a total of 20 asylum seekers.

I sing You a hymn, Unknown God,

For me, though You’re vanishing ages’ lugubrious mystery;

You—a crossroad on wandering earth's orbit

Where my troubled thought returns now and then.

For some, You are stormy thundering revelation,

For others, the voice that breaks midnight’s towering silence.

But for me—the ruins of a sanctuary, this earth

Where nature’s teeming life reveals nothing at all.

For me, You are distant so many bright years, like a star

To whose miraculous light I am blind.

Perhaps your glance intermingles there with the fires,

But here—I do not fear You, nor love You.

I, a dustmote of sun-consumed wastelands.

I know that You are; not who You are, how You are —

My heart, before the thought of eternity

That I seek for in galaxies, is silent.

It may be that only in earth’s hollowed grave,

If I rise someday through the dews, a sunny blossom,

That here, among earth’s fragrant flowers,

I will see my Unknown God.

—Putinas (1893-1967)

The native peoples of Lithuania and Latvia were the last in Europe to convert to Christianity. Independent Baltic tribes worshiped the sun and wind, held as holy the woods and rocks and rivers of the wild coast, and preserved their mythology through sacred hymns called dainos.* Their pantheon is familiarly Indo-European: the supreme sky god Dievas (related etymologically to deity, deus, and the Hindu deva), the solar goddess Saulė (a match for the Vedic Surya), and Perkūnas the thunder god (similar in representation to Zeus and Thor).

The history of Baltic Christianity is one of savage northern crusades and forced conversions, and the crossroads town of Šiauliai illustrates its violence and superficiality. The Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul stands on the site of an ancient shrine where high priests burned sacrifices to the gods—including the occasional Teutonic Knight. A sun intersects its crosses and recollects Dievas and Saulė. Its cemetery, in a hilly and once sacred grove, flickers with candlelight on the Day of the Dead in November, which takes its local name, Vėlinės, and much of its local character from the cult of Veliona, guardian of souls.

The national awakening of Baltic peoples in the nineteenth century ushered a revival of pre-Christian belief and practices, alongside other folk traditions. Founders of Romuva and Druwi in Lithuania and the Dievturi movement in Latvia framed their reconstructions as returns, though they often borrowed as much from popular Hindu and Buddhist concepts as from the fragmentary evidence of the ancient Balts.

*Igor Stravinsky borrowed elements of “The Rite of Spring,” his paean to pagan days, from Lithuanian dainos.

But some keep bending their backs up to the last

pail in hand until they die aghast

they draw and draw and never know from what

they pour and such and never know for what

year chases year and half their life is over

is old age coming no old age passes them over.

they start to boast of who and what they’ve been

what they have done and what they’ve seen

they hold on to their things (but they rot and rust)

year chases year till the cup it runneth ov’r.

—Uldis Bērziņš (b. 1944)

Amber was one of the first commodities of long-distance trade in Europe, valued since the Stone Age for its color, its beauty, and its light weight. Over 90 percent of the world’s amber is found along the Baltic coast of Latvia, Lithuania, and especially Russian Kaliningrad, where the fossilized pine resin washes ashore after being torn from the seabed by storms and tides, often in massive quantities. A single morning in 1862 saw 2,000 kg (4,400 lbs) collected from a Samland beach.

Ancient traders moved from north to south along the so-called Amber Road: by the Vistula and the Dniestr to the urban centers of the Mediterranean, where their merchandise ended up in the ornaments of Tutankhamen, the beehive tombs of Mycenae, and the treasury of Delphi.

Tacitus remarks on the bewilderment of the Aesti amber-gatherers that anyone would want to buy something so abundant, much less pay so dearly. The dress of an Aesti commoner, woven with beads of this “northern gold,” might fetch a fortune in Rome by the wonders of international commerce. Amber remains a feature of Baltic folk costumes and a staple of old town tourist shops.

I am a citizen of the world, known to all and to all a stranger.

—Desiderius Erasmus (1456-1536)

The Erasmus mobility program is named after that broadly European scholar of Renaissance humanism, with a backronym taken to be “EuRopean community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students.” Students from the 37 participating countries are able to spend three months to a year studying in another country in Europe, with the goal of developing a practical working knowledge of European ways and cultivating a European citizenship identity.

The meaning of these terms is complex and historically contested. However, the effectiveness of Erasmus is hard to deny, inspiring its not unwarranted description as “the single most successful component of EU policy” and the increasingly commonplace reference to an “Erasmus Generation.” Erasmus has engaged over three million students since its 1987 establishment, including five percent of European graduates in 2012. Early research suggests that more of those students identify as citizens of Europe than of their country, citing common values and manners, the European Union project, travel experience, languages, relationships, and a negative reaction to nationalism at home.

But let’s not yearn for the days of prenormalization.

Just think of the torments, the anxieties, the sweat,

the wiles needed to entice, in spite of all.

—Czesław Miłosz (1911-2004)

In The Irony of Fate (1976), a Soviet-era made-for-TV romcom of enduring popularity, Zhenya awakens in the wrong town after New Year’s Eve in a banya. Unaware, he gives his address on Construction Worker’s Street to a taxi driver and arrives at a different street with the same name and aspect, walks to an apartment building identical to his, and opens the front door with a key that fits the standardized lock. The layout and even the furniture is familiar—this in the days before Ikea. But of course the apartment belongs to a beautiful stranger, and when she returns hijinks ensue.

The scenario hit a mark all over Eastern Europe, where millions of people lived in apartments just like Zhenya’s. The 5- to 16-floor public housing blocks called Khrushchyovkas are named for the party leader who initiated their construction to resolve a severe housing crunch in the capital. The application of industrial techniques to residential buildings turned construction into a task of assembling prefabricated parts, mostly concrete panels, in standardized sections with very little deviation from Krushchev’s drab but functional prototype. Arranged in microdistricts inspired by the ville radieuse of Le Corbusier, surrounded by plenty of green space and parks, the Khrushchyovka arose with a previously unimaginable rapidity across the USSR.*

The Khrushchyovka had two problems. First, it gave a grey uniformity to Eastern Bloc cities that might align with socialist propaganda but could only depress the actual human beings living there. Second, the buildings had an intended lifespan of 20 to 25 years and were poorly maintained. In 2017 Moscow announced that it would demolish 8,000 Khrushchyovka (and displace 1.5 million people) out of a preference for higher and more densely-packed domiciles. East Germany has already replaced most of theirs. In other places, the collapse of the USSR saw a drive toward expression which decorated the old concrete structures in flamboyant colors.

What is needed most, here as in any locality where history is associated with backwardness, is an effort at preservation.

* Housing blocks built under Brezhnev were called Brezhnevkis, though very little distinguishes the second-generation design from the first.

For you, a cinema spectacle

For me, almost a Weltanschauung!

The cinema—purveyor of movement

The cinema—renewer of literature

The cinema—destroyer of aesthetics

The cinema—fearlessness

The cinema—a sportsman

The cinema—a sower of ideas.

But the cinema is sick.

Capitalism has covered its eyes with gold . . .

Communism must rescue the cinema from speculators.

—Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930)

“Of all the arts,” wrote Lenin, “for us the cinema is the most important.” Soviet cinema was an instrument of the Soviet state, under the control of the education ministry, the political police, and eventually the State Cinema Board, Sovkino. As a vehicle for propaganda, it had a far wider reach than literature or newsprint. It was also a young industry—the first Russian feature film, 1908’s Sten’ka Razin, was released within ten years of the Bolshevik takeover in 1917—and unlike more developed institutions, the communists had little trouble in shaping it to their needs.

Most Soviet films were works of socialist realism or celebrations of victory in the Great Patriotic War. The former was a plastic genre whose essential tenet was conformity to this or that party leader, despite the plaintive declarations of theorists like Alexei Gan that “cinema should depict our way of life!” The latter was, and remains, a means of embellishing national victories and of erasing national wrongs. “But there were shafts of light amidst the gloom,” notes Norman Davies.

Sergei Eisenstein proved “that great art is not incompatible with overt propaganda” with the six films he directed, including Battleship Potemkin (1925), October (1927), and Alexander Nevsky (1938). Kalatozov’s The Cranes are Flying (1957) and Bondarchuk’s four-part War and Peace (1966-1967) are associated with Khruschev’s “Thaw.” And Andrei Tarkovsky felt the freedom to begin questioning the structures which cinema had largely inherited from literature and theater in Mirror (1975). He filmed Stalker (1979) at two deserted hydroelectric plants on the Jägala River near Tallinn, Estonia.

“Art must give man hope and faith,” wrote Tarkovsky in his cinematic credo Sculpting in Time. The goal of all art worthy of the name is “to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence . . . or if not to explain, at least to pose the question.” Art does not propagandize easy answers or ideologies—“The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good. Touched by a masterpiece, a person begins to hear in himself that same call of truth which prompted the artist to his creative act.” The artist is a priest whose mission it is to reveal the beauty that is “hidden from the eyes of those who are not searching for the truth.”

Dearer to me than a host of base truths is the illusion that exalts.

—Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin (1799-1837)

Knighthood was reborn in Russia as a full-contact sport, fully armored and historically correct. From there it returned to Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic states, then to Central and Western Europe before spreading abroad. Combatants wear custom steel plate usually based on 14th and 15th century designs and weighing as much as 80 pounds. Their blades are dull, the length and width carefully governed: the rule sheet of the US-based Armored Combat League runs to 40 pages, including appendices. Matches range from point-based professional duels to large-scale melees of three- to 21-person teams, where the goal is to ground opponents.

“Historical Medieval Battles” is perhaps more UFC than Ivanhoe. Other than fencing and unlike the martial arts of Japan, Europe’s pre-modern fighting traditions were mostly lost. Medieval handbooks and historical accounts tend to skim over general details that would have been obvious to contemporaries, leaving gaps in our understanding of how knights fought. Nevertheless its modern incarnation has something to teach.

The weight and heat of steel exhausts the armored combatant, and a five-minute contest can bend even the best. Equipment requires constant adjustment and tightening. Its edges, especially the gauntlet and the boot, are as useful as the sword, and the push and grapple are even more common than the graceful parry. Modern fighters respond to old problems, but it cannot be known whether the solutions—the heavily padded helmets, the habit of resting the sword on the shoulder between exchanges, the use of the foot to block—are traditional or innovative.

One clear continuity is its universality. Chivalry, that prevailing ethos of Europe’s feudal society, bound with common ties warriors of every nation and condition, and enrolled them in a vast fellowship of manners, ideals, and aims—“the pursuit of adventures under Mars and Venus.” That admittance was even broader at the Old Tallinn Tournament, with women making up more than half of those on the field. The games pitted against each other, in matches of singles and three-on-three, knights from Estonia, Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania, the Holy Land, and China, and whatever rivalries may obtain, noble cheer was evident in all.

Comments

Post a Comment